This whitepaper is for historical reference only. Some content might be outdated and some links might not be available.

The initial motivation

To understand SaaS, let’s start with a fairly simple notion of what we’re trying to achieve when creating a SaaS business. The best place to start is by looking at how traditional (non-SaaS) software has been created, managed, and operated.

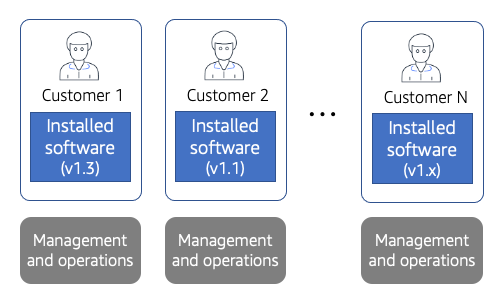

The following diagram provides a conceptual view of how several vendors have packaged and delivered their solutions.

The classic model for packaging and delivering software solutions

In this diagram, we’ve described a collection of customer environments. These customers represent the different companies or entities that have purchased a vendor’s software. Each of these customers is essentially running in a standalone environment where they have installed a software provider’s product.

In this mode, each customer’s installation is treated as a standalone environment that is dedicated to that customer. This means that customers view themselves as the owners of these environments, potentially requesting one-off customization or unique configurations that support their needs.

One common side effect of this mindset is that customers will control which version of a product they are running. This could happen for a variety of reasons. Customers might be apprehensive about new features, or worried about disruptions associated with adopting a new version.

You can imagine how this dynamic can impact the operational footprint of the software provider. The more you allow customers to have one-off environments, the more challenging it becomes to manage, update, and support the varying configurations of each customer.

This need for one-off environments often requires organizations to create dedicated teams that provide separate management and operations experience for each customer. While some of these resources might be shared across customers, this model generally introduces incremental expenses for each new customer that is onboarded.

Having each customer run their solutions in their own environment (in the cloud or on premises) also impacts cost. While you can attempt to scale these environments, the scaling will be limited to the activity of a single customer. Essentially, your cost optimization is limited to what you can achieve within the scope of an individual customer environment. It also means that you might need separate scaling strategies to accommodate the activity variations between customers.

Initially, some software businesses will view this model as a powerful construct. They use the ability to provide one-off customization as a sales tool, allowing new customers to impose requirements that are unique to their environment. While the customer count and growth of the business remains modest, this model seems perfectly sustainable.

As companies begin to have broader success, however, the constraints of this model begin to create real challenges. Imagine, for example, a scenario where your business reaches a significant growth spike that has you adding lots of new customers at a rapid pace. This growth will begin to add to the operational overhead, management complexity, cost, and a host of other issues.

Ultimately, the collective overhead and impact of this model can begin to fundamentally undermine the success of a software business. The first pain point might be operational efficiency. The incremental staffing and costs associated with bringing on customers begins to erode the margins of the business.

However, operational issues are just part of the challenge. The real issue is that this model, as it scales, directly begins to impact the business’s ability to release new features and keep pace with the market. When each customer has their own environment, providers must balance a host of update, migration, and customer requirements as they attempt to introduce new capabilities into their system.

This typically leads to longer and more complex release cycles, which tends to reduce the number of releases that are made each year. More importantly, this complexity has teams devoting more time to analyzing each new feature long before it’s released to a customer. Teams begin to be more focused on validating new features and less on the speed of delivery. The overhead of releasing new features becomes so significant that teams become more focused on the mechanics of testing, and less on the new functionality that drives the innovation of their offering.

In this slower, more cautious mode, teams tend to have long cycle times that put larger and larger gaps between the inception of an idea and when it lands in the hands of a customer. Overall, this can hinder your ability to react to market dynamics and competitive pressures.