Agents meet multi-tenancy

It's easy to think of agents as building blocks where agents are viewed as a series of autonomous components that are assembled to support the needs of a specific domain or business problem. Where it gets more interesting is when we start to think about how these agents are packaged and consumed by providers. In many respects, an agent becomes a source of cost and revenue for a business. Agent providers must consider the different personas that consume their services, the consumption profile of the personas, and the monetization strategies that allow agent providers to create pricing and tiering models that align with consumers.

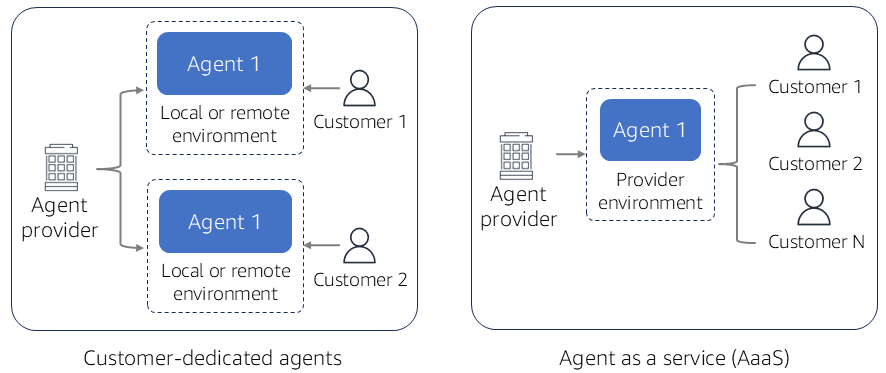

Agent providers could support multiple models for deploying their agents to meet customer needs. The following diagram shows a conceptual view of the two main agent deployment models.

The left-hand side of the diagram shows the customer-dedicated agent model. An agent provider builds an agent by deploying a separate agent instance for each onboarded customer. With this approach, the capabilities of the agent and its ability to acquire knowledge would be limited to the scope of a given customer's environment. This ends up representing a per-customer experience that inherits some of the complexities and advantages of supporting dedicated customer environments.

In contrast, the diagram on the right-hand side of the diagram has a single agent that is deployed in the provider's environment. The agent processes requests from multiple customers, evolving and learning based on the collective experience of all customers. Each new customer that's added would simply represent another valid client of the agent. The agent runs like an agent as a service (AaaS) model, using shared constructs to support a client's needs. In both instances, agent consumers can be applications, systems, or even other agents.

There are two ways you can look at the AaaS model. The model above delivers the same experience to all customers. This means the internals of the agent will not include any level of specialization that considers the context of the requesting client. Generally, for this mode, the assumption is that the nature of an agent's scope, goals, and value centers around a shared set of resources, knowledge, and outcomes that are applied universally to all clients.

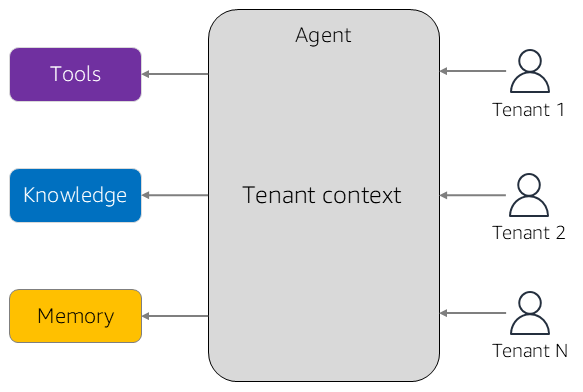

The alternative approach to AaaS is where the context of clients influences the agent's experience and implementation. The following diagram provides a conceptual view of an AaaS agent footprint in this context.

In this AaaS view, the origin and context of the incoming requests significantly affect the agent's footprint. The resources, actions, and tools that are part of the agent's underlying implementation may vary for each incoming tenant request. The value of an agent is connected to its ability to use tenant context to arrive at actions and outcomes that are influenced by tenant state, knowledge, and other factors. Some requests may yield a unique tenant outcome, and others may lead to more tailored per-tenant outcomes. This adds a new dimension to the agent's ability to learn, which could include being more contextual and acquiring and applying knowledge that enhances targeted outcomes.

For providers, the AaaS model offers many advantages. With multiple customers consuming a single agent, the provider has a better opportunity to achieve economies of scale, drive operational efficiency, control costs, and create a unified management experience. This has the potential for greater agility, innovation, and growth for the agent business.

These qualities overlap with the same principles that drive the adoption of the software as a service (SaaS) model. Essentially, the AaaS model is built as a multi-tenant service that inherits many of the same scale, resilience, isolation, onboarding, and operational attributes that are found in a SaaS environment. In many respects, the AaaS experience borrows heavily from the strategies and practices used by SaaS providers, but it's reasonable to separate these terms. For our purposes, the emphasis is mostly on the implications that come with building and operating agents that require multi-tenant support.

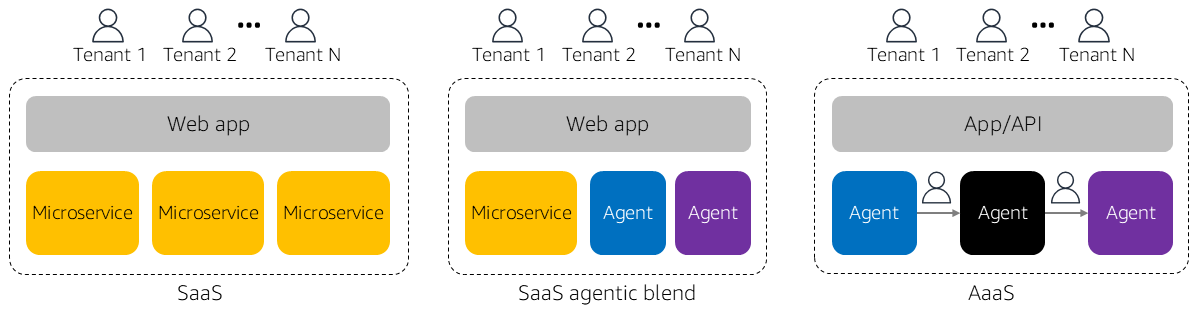

For a system that can treat all users equally and doesn't require the management of persistent, sensitive, or customer-specific data, the notion of tenancy would minimally affect their agents. For systems that are expected to serve multiple customers while preserving data isolation, customization, and context awareness, supporting multiple tenants could be an essential element of an agent's design, strategy, and goal. The following diagram shows how multi-tenancy can be used in agentic environments.

On the left-hand side of this diagram is a classic multi-tenant architecture. It includes a web application and a series of microservices that implement business logic. Multiple tenants consume the shared infrastructure of this environment, scaling to meet the shifting workloads of a tenant population that evolves. The environment is operated and managed through a single pane of glass for all tenants.

Imagine how this mental model maps to the agent on the right-hand side of this diagram. One agent runs an AaaS model that's consumed by one or more tenants. The agents could be from multiple providers with tenant context flowing between them because a single instance of one agent must process requests from multiple tenants.

The example in the middle of this diagram is a hybrid model where agents are part of the overall SaaS experience. Some parts of the system are implemented in a more traditional model and other parts of the system rely on agents. This pattern is likely to be common for many SaaS offerings—especially for organizations that are transitioning to an agentic experience. It's common for this model to persist because not all systems are delivered as pure AaaS. Also note that multi-tenancy still applies to the model's agents. While the agents may be embedded within a system, they may still process requests from multiple tenants.

It's natural to ask whether multi-tenancy really matters. You could argue that an agent processes requests, so supporting tenancy may have little effect. But as we dig deeper into multi-tenant agentic implications, tenancy may directly affect how agents influence how tools, memory, data, and other agent parts are accessed, deployed, and configured to support individual tenants. Tenancy also influences how scaling, throttling, pricing, tiering, and other business aspects apply to your agent's architecture.

One takeaway from this is that there are agentic use cases that require multi-tenancy support. The challenge is to determine how multi-tenancy shapes the overall design and architecture of your agentic experience. For some agents, multi-tenant support represents a differentiating capability, allowing agents to apply tenant-specific context to agents that deliver targeted outcomes.

In subsequent sections, you'll see how the terminology and design patterns that we create to describe multi-tenant SaaS architectures will be useful. These concepts can be adopted by the AaaS model by borrowing useful aspects, which introduces new agent-specific concepts where they're needed.

Identity, tenant context, and agentic systems

Adding tenant context to individual agents isn't particularly challenging. In many instances, teams can rely on typical mechanisms that bind users and systems to tenants and pass tenant-aware tokens to agents. This is relevant when we consider how tenant context and identity supports multiple agents. In this model, tenants must be bound to an identity that spans all collaborating agents.

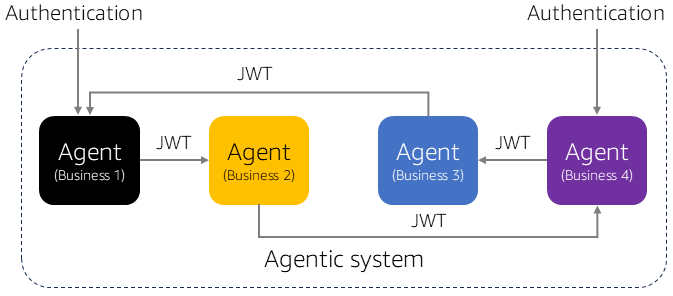

In general, the agentic domain requires a more cross-cutting identity model that aligns with the current and emerging needs of agentic systems. Agent providers require identity mechanisms that support unique security, compliance, and authorization models that come with operating agentic systems. This is especially challenging in environments where systems are composed by customers or other agents. Each onboarded agent must connect its identity and tenant context to agent interactions. The following diagram highlights the potential identity and tenant context challenges that are part of agent-to-agent (a2a) interactions.

This diagram shows a series of provider-built agents interacting as part of the agentic system we covered. It's now retrofitted with identity and tenant context. This scenario is an example of an agentic system that supports multiple entry points. We assume that each agent in this system requires its own authentication mechanism to resolve the system or user to a given tenant. As these agents interact, tenant context is passed to a JSON web token (JWT) that will be used to authorize access and inject tenant context into the agent.

Conceptually, the main difference with this scenario is that agents deploy and operate independently, which means that each agent must be able to resolve its identity and authorize access. The key is that its identity must have some distributed ability to handle the needs of the broader agentic system. There must also be alignment on how agents share tenant context.

Applying SaaS business value to AaaS

Generally, when we look at running any system in an as-a-service model, we consider the nature of the experience and how its technical and operational footprint drives business outcomes. When adopting SaaS, for example, organizations use economies of scale, operational efficiencies, cost profiles, and agility to drive growth, margins, and innovation.

Agents delivered as AaaS are likely to target similar business outcomes. By supporting multiple tenants, an agent can align resource consumption with tenant activities. This yields economies of scale that come with traditional SaaS environments. AaaS also allows organizations to manage, operate, and deploy agents in a way that enables frequent releases and drives agility for agent providers. The key is that the AaaS model doesn't depend on technology. It creates and drives business strategies that promote growth, streamline adoption, and simplify operations.